Decentralized Elections in the U.S.: A Strong Defense Against Fraud

As debates around the security of U.S. elections persist, particularly after the 2020 presidential race, the resilience of America’s decentralized election system emerges as a key pillar of integrity. In contrast to nations with a single centralized authority, the U.S. operates a multifaceted electoral framework managed by states and counties, creating numerous safeguards against fraud.

Steve Kornacki, renowned as the NBC News and MSNBC political correspondent for his electoral map analyses, emphasizes the robustness of this decentralized system in enhancing election security. “What it ends up creating is this vastly decentralized system,” Kornacki said on “The Poynter Report Podcast.” While this organization may introduce delays and inconsistencies, it effectively acts as a barrier to large-scale tampering.

Kornacki highlighted that fears about election security often stem from the potential for coordinated manipulation. He explains that the fragmented nature of U.S. elections makes widespread interference challenging. “It’s not like there’s one central nerve that you can kind of disrupt that’ll change the election result all across the country,” Kornacki noted, stressing that any attempt to alter election outcomes would necessitate efforts across thousands of precincts nationwide, thus complicating any manipulation attempts significantly.

Pennsylvania’s Localized Election Structure: An Example of Fraud Prevention

In Pennsylvania, following claims of election fraud during the 2020 presidential election, attention has turned to the state’s decentralized electoral system. Critics, including former President Donald Trump, have alleged widespread fraud. However, experts point to the state’s decentralized election administration as a vital countermeasure.

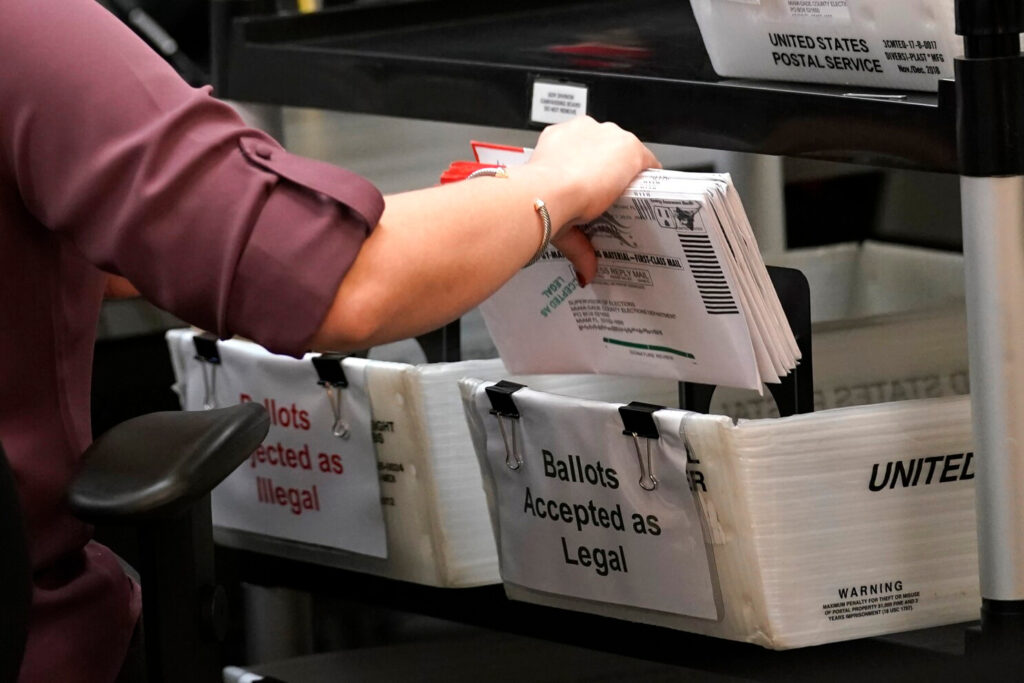

Thad Hall, election director in Mercer County, underscores that Pennsylvania’s electoral system, with its strong local focus, renders large-scale fraud improbable. He noted, “When you claim that mail ballots were mishandled, the people that would do that would be residents of Mercer County,” suggesting that such widespread misconduct would require collaboration across political lines, which is unlikely.

Pennsylvania’s elections are managed through a three-tier system involving the Department of State, county officials, and local poll workers. The Department of State handles voter registration and certifies results, while county officials manage voting machines. Local poll workers, drawn from the community, ensure election procedures are followed on Election Day.

This decentralized framework grants Pennsylvania’s 67 counties significant flexibility, such as using drop boxes or correcting mail ballot errors. While state laws provide foundational guidelines, counties adapt practices to local contexts. Each county’s board of elections, elected locally, is responsible for interpreting laws and making policy decisions.

The complexities of Pennsylvania’s electoral system demand cooperation among local officials. Elected county boards interpret state laws and make policy choices, relying on court rulings and legal advice. The Department of State offers guidance where needed. Election directors, appointed by counties, manage operations, including polling place organization and ballot counting, ensuring legal compliance.

In the latest election, Pennsylvania deployed approximately 9,000 polling places staffed by nearly 50,000 poll workers, reflecting extensive community involvement. Registered voters can apply to become poll workers, fostering local engagement in elections. Training is provided to equip poll workers for their roles effectively.

Community involvement is crucial for secure voting. Each precinct has a lead election officer, known as the judge of elections, who handles issues, monitors voter numbers, and secures ballots. Inspectors assist with registration and equipment, with all positions elected every four years.

The distributed nature of elections in Pennsylvania, characterized by local oversight and community participation, not only boosts security but also acts as a formidable defense against large-scale manipulation. Kornacki aptly describes it, stating, “It’s not like there’s one central nerve that you can disrupt to change the election result all across the country.”

By embedding community participation at all levels—from state oversight to local poll workers—the integrity of the electoral process is fortified. This approach reassures voters that their elections are secure and their voices count in the democratic process.